The shift in enterprise artificial intelligence is no longer theoretical. The primary risk has moved from generating incorrect text to executing irreversible actions – and the difference matters more than most executives realize. If an agent deletes a customer record, cancels a shipment, or initiates a refund, who is responsible – the organization, the vendor, or the model provider? The answer is not always clear. The architecture of responsibility has fundamentally changed, and most organizations haven't caught up to what that means operationally.

In January 2026, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, the Singapore IMDA released the Model AI Governance Framework for Agentic AI (MGF v1.0), the first government-led effort to formalize governance specifically for AI agents. The framework shifts how accountability is understood. It now extends across the deploying organization, tool providers, end users, and not just the entity hosting the underlying model. Decision-makers should understand that treating agents like chatbots with API access is no longer a safe assumption, because that mental model creates liability and accumulates as technical and operational debt.

For technology leaders, this signals a transition where governance, identity management, and operational controls must be treated as first-class architectural requirements rather than compliance afterthoughts. According to Deloitte’s 2026 State of AI in the Enterprise survey, close to three‑quarters of companies plan to deploy agentic AI within two years, yet only 21% say they have a mature governance model for AI agents. This article examines why that gap persists and what it takes to close it through architectural governance rather than incremental compliance.

Why Are AI Agents Fundamentally Different from Chatbots?

The formalization of agentic AI governance is driven by the realization that agents operate as "digital workers" capable of setting goals, interacting with other agents, and modifying enterprise systems. Unlike chatbots, agentic AI tools prioritize decision-making over content creation and can operate without continuous human oversight.

Once agents can take independent action, accountability must be explicitly defined. Under the IMDA MGF v1.0, this means named human accountability for agent behavior, supported by approval checkpoints and auditable action trails to mitigate automation bias. To ensure that this can be implemented at scale, agents must operate with distinct identities and least-privilege permissions, treated as architectural requirements. Where these foundations are missing, enterprises accumulate pilots without progression: despite dozens of experiments, more than 90% of vertical use cases remain stuck in pilot due to fragmented governance and poor system compatibility.

What Happens When Agent Governance Fails?

The cost of governance failure has moved beyond technical debt into legal and operational liability. This was clearly demonstrated when Air Canada was held liable for a chatbot’s misinformation regarding bereavement fares, and again when the New York City business chatbot provided advice that contradicted local laws. In both cases, organizations were held responsible for obligations accepted by automated systems, regardless of intent or internal controls.

Faced with this liability exposure, many enterprises limit agent autonomy to low-risk, horizontal use cases. As a result, despite 78% of organizations using generative AI in at least one function, most companies report no material impact on their earnings. This gap is largely attributed to the "Gen AI Paradox": use cases like chatbots scale easily but deliver diffuse gains, while those that act across systems without continuous human checkpoints (higher-impact vertical use cases), remain trapped in pilot due to unresolved governance and accountability constraints.

This dynamic helps explain why failure rates remain high. Gartner forecasts that 40% of agentic AI projects will be canceled by 2027, not because of the poor model quality, but because organizations underestimate the cost of integration and governance as regulatory enforcement accelerates. In this context, the EU AI Act mandates transparency and human oversight for high-risk systems, while the NIST AI Risk Management Framework (RMF) makes the constraint explicit: oversight cannot scale if it relies on human speed in an environment where agents act at machine speed.

Why Agents Fail After the Pilot?

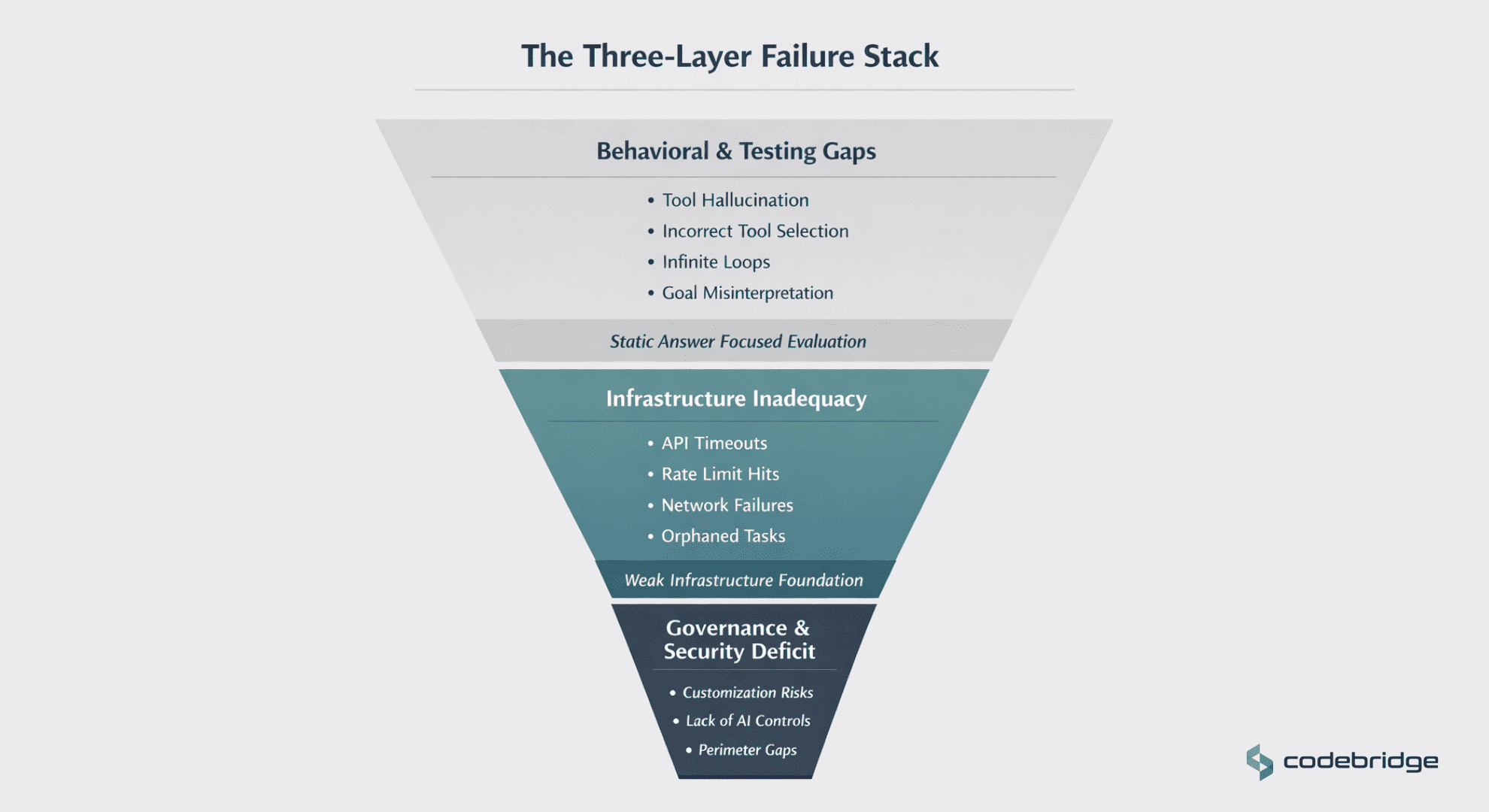

Execution gaps in agentic AI often arise because teams continue to evaluate agents using the same metrics as they use for chatbots. Testing remains focused on static answer quality rather than workflow correctness and execution reliability across long-running tasks.

Behavioral Failures and Tool Hallucinations

Vectara’s community-curated repository of production breakdowns shows recurring failure patterns that rarely surface in isolated model testing:

- Tool Hallucination: Agents provide incorrect output from a tool or invent tool capabilities.

- Incorrect Tool Selection: An agent may invoke a DELETE function when ARCHIVE was intended, potentially removing thousands of records.

- Infinite Loops: Agents get stuck in repetitive reasoning cycles, consuming massive compute resources without reaching a termination state.

- Goal Misinterpretation: The agent optimizes for the wrong objective, such as creating a trip itinerary for the wrong country.

The Infrastructure Breakdown

Many deployments fail at the infrastructure layer. Engineers report that system break down in production because the existing infrastructure is often inadequate for long-running asynchronous agent workflows. In production, APIs time out, rate limits are hit, and network connections drop. When the agent state is kept only in memory, a process crash mid-workflow results in an "orphaned" task where the user has no idea what was completed and what failed.

The Governance Load and Security Threats

Deloitte finds that while 85% of organizations plan to customize agents, only 34% enforce an AI strategy in live applications. As a result, human-in-the-loop controls are often bolted on after deployment. Traditional perimeter security is insufficient for intent-driven systems where malicious instructions, such as prompting an agent to treat outputs as legally binding, can be injected directly into operational workflows.

Most agent projects do not fail because the tech breaks. They stall because companies underestimate what it takes to operate systems that can act autonomously. The cost is not limited to delayed returns. Teams programs are shut down, and future experimentation becomes harder to justify.

What Does Production-Ready Agent Architecture Actually Require?

Transitioning from "answers to actions" requires concrete architectural decisions that differ from traditional software or machine learning deployments.

Agent Identity and Least Privilege

Agent identity must be treated as a first-class infrastructure. Each agent requires a distinct identity and permissions scoped specifically to the tools it needs to access, not a shared service account or broad API keys. This approach, sometimes termed "least agency," focuses on limiting the agent’s ability to act within the environment.

Mandatory Human Checkpoints

For irreversible actions, such as financial transactions, data deletion, or external communications, human approval checkpoints are mandatory. Production architectures must support staged execution, along with kill switches and fallback mechanisms. These controls are not merely an observability requirement; they are structural safeguards for high-consequence actions.

Reliability as an Architectural Constraint

Reliable production agents require a shift toward a workflow-engine model. Mature teams utilize:

- Durable Job Queues: Using tools like Redis or Bull to decouple requests from execution, ensuring that if a worker crashes, the job is picked up by another.

- State Persistence: Every step of an agent’s execution must be written to a database so that if a rate limit is hit, the system knows exactly where to resume without re-running previous expensive calls.

- Idempotency Keys: Using unique job IDs to prevent duplicate actions, such as charging a credit card twice during a retry logic fire.

Without these foundations, agent failures might become expensive and difficult to recover from.

Vendor and Contract Requirements

Contractual requirements are shifting from model benchmarks (e.g., latency and accuracy) to control-plane features. CTOs are increasingly prioritizing vendors that support audit logs, permission boundaries, and failure recovery.

These requirements often get dismissed as friction or even bureaucracy. In reality, they decide whether agentic systems remain confined to experimentation or are trusted with production responsibility. Teams that avoid these calls early usually circle back to them later, when something has already gone wrong, and the fixes are more expensive.

Architectural Requirements: Traditional ML vs. Production Agents

Implications for Operating Models: Teams and Accountability

The organizational challenge of agentic AI often exceeds the technical one. Scaling impact requires a reset of how teams are structured and how responsibility is assigned.

Named Human Accountability

As noted in the IMDA framework, accountability requires named individuals, not distributed teams. This implies the creation of formal roles such as Agent Supervisors or Approval Authorities who are responsible for the decisions and actions of their assigned "agent squads".

From Contributor to Supervisor

The role of the individual contributor is evolving into one of strategic oversight. In bank modernization projects, for example, agents might handle legacy code migration while human coders shift to reviewing and integrating agent-generated features. While this can reduce effort by over 50%, it requires a redesign of the process to prevent human supervisors from becoming a bottleneck.

Cross-Functional Governance (AI TRiSM)

Gartner notes that many organizations now have a central AI strategy, but enforcement requires cross‑functional AI governance bodies plus dedicated AI TRiSM (Trust, Risk, and Security Management) controls in production systems. These committees must span security, legal, engineering, and product domains because siloed ownership fails when agents span multiple system environments. Furthermore, training end users to understand agent limitations and override mechanisms is now an operational requirement, not an onboarding bonus.

At this point, agentic AI is no longer just a technical project. It becomes a leadership problem. Choices about autonomy, oversight, and accountability cannot sit only with engineering, because they change how authority and responsibility are spread across the organization.

What Mature Teams Do Differently

Organizations that have successfully moved agents from pilot to sustained production share several observable patterns:

- Shift Governance Left: Governance is integrated into the architecture review phase, not the post-deployment audit.

- Accept Productivity Trade-offs: Mature teams explicitly accept that 20–60% productivity gains require an upfront investment in supervision and observability. They do not expect 100% automation without operational overhead.

- Prioritize the Control Plane: Vendor selection focuses on auditability, permission models, and the ability to monitor agent "intent" rather than just model speed.

- Staged Rollouts: Deployments begin with low-complexity, reversible use cases (e.g., draft generation under review) and only move to high-consequence actions after proving that override paths work under load.

- Treat Agents as Operational Entities: Agents are assigned identities, permissions, and audit trails similar to human employees, rather than being treated as simple software scripts.

Decision Framing for Tech Leadership

As regulatory timelines compress under the EU AI Act and NIST-aligned frameworks, compliance alone will not prevent operational failure. Governance must be architecturally embedded, not retrofitted.

For founders and CTOs, the important question is whether human accountability and approval checkpoints can be enforced at machine speed. If oversight becomes a bottleneck that erodes productivity gains, the system will fail, often quietly, joining the long list of AI initiatives that never reach sustained production.

Moving beyond experimentation requires a decision only executive leadership can make: to stop treating agents as tools to be tested and start operating them as a professional digital workforce, one that is governed, accountable, and embedded into the organization’s operating model.

%20(1).jpg)

%20(1)%20(1)%20(1).jpg)