According to Harvard Law School, approximately 75% of venture-backed startups fail, meaning they do not reach an exit that returns capital to all equity holders.

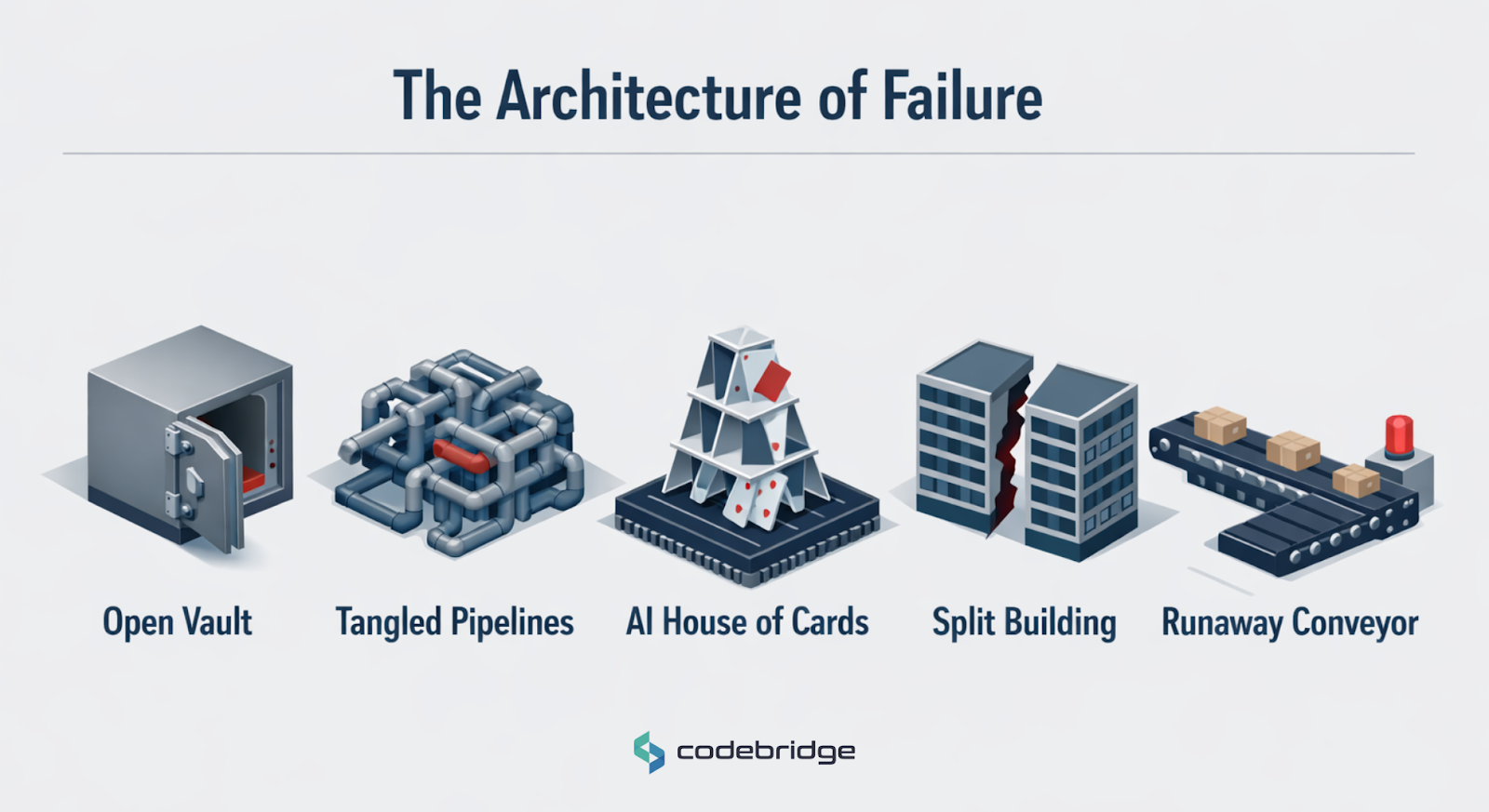

Startup failures are often blamed on market fit, funding, or competition, but these labels hide deeper structural problems. However, many companies fail not because their idea is wrong, but because the systems they build cannot safely support the business model they depend on.

This article examines five companies whose collapse was driven primarily by technical and product decisions rather than marketing mistakes or lack of demand. The goal is not retrospective judgment. Rather than assigning blame, this article identifies recurring technical patterns that lead to collapse.

1. Mt. Gox: When Security Was an Afterthought

At its peak, Mt. Gox was the world’s dominant Bitcoin exchange, facilitating over 70% of all global transactions. However, in 2014, it collapsed after losing approximately 850,000 Bitcoin, valued at $450 million at the time and more than $50 billion today.

At the time, Mt. Gox was the only liquid and accessible venue where early adopters could convert mined or purchased Bitcoin into fiat currency. Before the emergence of Coinbase, Binance, or meaningful regulation, it functioned as the primary bridge between the traditional financial system and the nascent crypto economy. Trust in Mt. Gox was not earned through superior design or controls – it was imposed by the absence of any viable alternative at scale.

The Fatal Decision

The exchange was operated largely as a one-person operation by leadership without institutional finance or security experience. Custody of hundreds of millions of dollars in value was treated as a secondary concern rather than the core product requirement.

Over several years, the system lacked the controls needed to detect unauthorized transfers. Funds were primarily held in a “hot wallet” permanently connected to the internet, where there was no reconciliation between database balances and blockchain balances. It allowed theft to go undetected for years.

What a Safer Architecture Would Have Required

This example gives modern founders something very practical to learn from. A financial system that holds customer assets has to be built around custody and control from day one, not secured later as the business grows. In Mt. Gox’s case, that would have meant:

- Keeping a real accounting ledger so internal balances were continuously checked against actual blockchain funds.

- Storing most assets offline and protecting access with multi-signature hardware security modules, instead of relying on a single connected wallet.

- Putting clear operational rules in place, including separated responsibilities, an auditable system change, and defined recovery procedures when something goes wrong.

CTO lesson: If your product holds real value, security isn’t something you add later. It is the product.

2. Primary Data: When Abstraction Becomes the Product

Primary Data burned through $100 million attempting to solve the “data gravity” problem, where large datasets tended to become trapped in legacy storage systems, not allowing them to be easily moved or accessed across different environments.

The company aimed to create a global data virtualization layer that would make data location-agnostic across storage systems such as NFS, SMB, block storage, and cloud platforms. It allowed its users to move and access data easily across hybrid and multi-cloud environments without requiring expensive migrations or changes to existing applications.

The Fatal Decision

However, the team made a critical mistake in how they approached the problem. Instead of narrowing their focus, Primary Data tried to abstract every type of storage system at the same time. That meant dealing with extremely hard problems around keeping metadata in sync and maintaining consistent behavior across storage technologies that were never designed to work the same way.

This design forced the entire system to operate at the speed and reliability of its weakest storage layer. When deployed in real enterprise environments, the software repeatedly ran into unpredictable edge cases in legacy hardware that it could not handle reliably. As a result, each implementation required heavy customization and hands-on services work, making it impossible for the product to scale as a true software platform.

What a Safer Architecture Would Have Required

This case shows why infrastructure products need clearly defined boundaries from the start. Rather than trying to hide every difference between storage systems, a safer approach would have focused on a limited set of scenarios and treated abstraction as a tool, not the goal itself.

In practice, modern solutions to data gravity work by accessing data where it already lives instead of trying to virtualize every storage layer into a single model.

Long-term growth would have depended on doing a few things extremely well before attempting to support everything. Expanding only after those core use cases were proven would have reduced complexity and improved reliability.

CTO lesson: The wider the abstraction, the harder it becomes to deliver a working system.

3. The Grid: When AI Became a Single Point of Failure

The Grid raised $4.7 million to build an AI-driven website design platform capable of generating sites automatically from content inputs.

The product was built on the idea that website design should not require technical skills or long development cycles. By applying artificial intelligence to the design process, it aimed to turn raw content into finished websites automatically, removing the need for professional designers or engineering work.

The Fatal Decision

The team built the product around AI as the final decision-maker, not as a tool to assist users. They assumed the system could generate acceptable designs without human input.

In reality, there was no reliable fallback when the AI made a bad decision. Because the system had no stable design framework underneath it, every result depended entirely on what the model produced. When the output was confusing or poorly structured, users had no way to fix it themselves. That inconsistency quickly drove people away and eroded trust in the product.

What a Safer Architecture Would Have Required

This case is highly relevant in our days of AI hype. It shows why artificial intelligence works best when it supports users instead of replacing them. A more resilient design would have kept humans in the loop and used AI to assist with decisions rather than dictate them. In practical terms, that would have meant:

- Giving users the ability to step in and adjust or override what the system produced.

- Building on top of a consistent layout framework so the product remained usable even when AI-generated results were imperfect.

- Treating AI as a recommendation engine rather than the only authority behind the final output.

CTO lesson: When the technology is still immature, it should strengthen the product – not become its foundation.

4. RethinkDB: When Infrastructure and Product Collide

RethinkDB was a distributed real-time database that failed after trying to operate simultaneously as a core database platform and a hosted service.

What They Built

The company tried to build a distributed, real-time JSON database designed for modern web applications. Its goal was to make it easier for developers to build responsive, data-driven products that could update in real time as users interacted with them.

The Fatal Decision

The company tried to develop both a core database product and a hosted service at the same time, without having separate structures in place to support each effort. Building a database engine and running a cloud service demands different kinds of work and different priorities.

As a result, engineering attention was divided between improving the stability of the database itself and adding features needed to operate the hosted platform. The ongoing demands of running the service slowed progress on the core technology. Meanwhile, competitors focused on doing one of these things well – either building strong databases or providing managed services – while RethinkDB continued to operate in the space between the two.

What a Safer Architecture Would Have Required

This case highlights how important it is to draw a clear line between the technology you build and the service you run on top of it. A more stable approach would have treated the database engine and the hosted service as separate concerns, each with its own goals and measures of success.

For most infrastructure startups, the safer path is to focus first on making the core technology truly solid before taking on the operational complexity of running it as a service. Expanding into operations only after the product itself is established reduces both technical and organizational strain.

CTO lesson: Building infrastructure and operating it are two different businesses, and they rarely succeed when treated as one too early.

5. ScaleFactor: When Automation Outruns Control

ScaleFactor burned $100 million building an automated bookkeeping platform for small businesses. It should have been a new alternative to traditional accounting firms using machine learning to automate bookkeeping.

The Fatal Decision

Leadership put too much faith in automation before the system had enough safeguards in place. The company focused on scaling sales and marketing while the reliability of its models lagged behind.

In real production, the machine learning system made mistakes that showed up directly in customer financial reports. Because there were no strong internal checks to catch those errors early, customers’ trust started to break down quickly. The team then had to bring in humans to fix what the automation got wrong, driving up costs and quickly draining the company’s remaining runway.

What a Safer Architecture Would Have Required

This case shows that in areas like accounting, full automation without oversight is risky by default. A more reliable approach would have kept people involved in the process and treated automation as something to supervise, not blindly trust. In practical terms, that would have meant:

- Keeping clear audit trails so that every automated decision can be reviewed and traced back.

- Defining confidence thresholds to decide when the system should proceed automatically and when it should pause.

- Routing uncertain or low-confidence cases to human reviewers instead of letting errors pass through unnoticed.

CTO lesson: When automation runs without controls, it breaks trust faster than doing the work manually.

Strategic Analysis: Common Failure Patterns

These cases show that startups rarely fail from lack of effort or flawed ideas. They fail due to structural mismatches between technological ambition and operational reality.

Universal solutions often become engineering tar pits by ignoring the constraints of legacy systems. Resilience comes from focus – supporting a few use cases well rather than many poorly.

Both The Grid and ScaleFactor assumed that technology performing well in controlled settings would survive real-world variance. Automation requires built-in checks and fallback paths.

Mt. Gox and RethinkDB illustrate how underestimating operational rigor leads to mechanical failure. Premature scaling of sales and marketing before technical foundations are secure is a persistent ecosystem risk.

Conclusion

For modern product teams – especially those building AI-powered or data-intensive systems – this implies several strategic realities:

- Architecture is strategy

- Automation requires governance

- Abstractions create obligations

- Trust depends on verifiable controls, transparency, and predictable system behavior

The most dangerous failures do not appear in demos. They emerge when products leave controlled environments and enter real operations: finance, healthcare, enterprise IT, and trust-based systems.

These failures are not warnings against innovation. They are warnings against unbounded systems. For technology leaders, that distinction separates growth from collapse.

%20(1)%20(1)%20(1).jpg)

.avif)